Profile of Anila Graham (1916-2004)

- ECOINT

- Jan 23, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 10, 2024

By Guilherme Sampaio | 2023

From the 1960s to the 1980s Graham published the following major texts:

1. Anila Graham, British Membership of the Common Market…What Will It Mean to India’s Trade (London: Economic and Development Research Limited, 1962).

2. Anila Graham, Break down the Barriers: Trade, Aid and International Development (London: United Nations Association of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 1964).

3. Anila Graham, International Liquidity and the Developing World (London: Economic and Development Research Limited, 1966).

4. Anila Graham, ‘The Aims and Activities of Unctad, Bank of London & South America Review, 1 (January 1968), 4.

5. Anila Graham, ‘The Transfer of Technology: A Test Case in the North-South Dialogue’, Journal of International Affairs (Spring–Summer 1979), 1–17.

6. Anila Graham, ‘Die neue internationale Wirtschaftsordnung—eine schwindende Vision?’, Vereinte Nationen: German Review on the United Nations, 27:5 (October 1979), 162–167.

7. Anila Graham, ‘Debt and Development: Need for Adequate Measures’, Development and Peace, 1 (Spring 1980), 106–117.

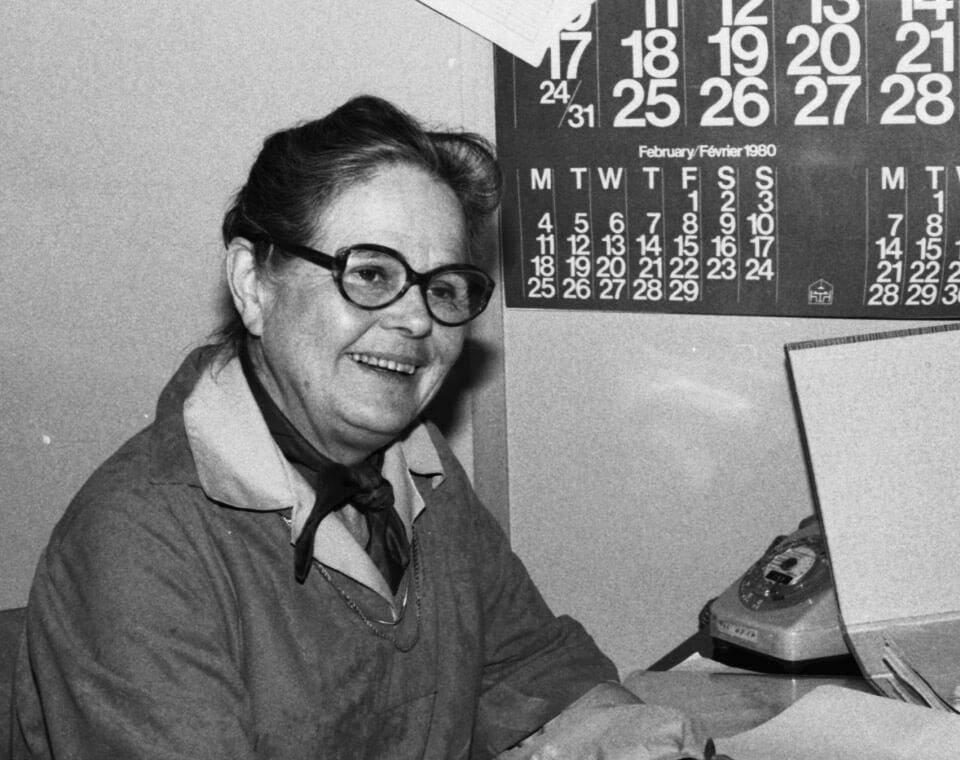

Anila Graham: Calling for a New International Economic Order (1916–2004)

Anila Graham (née Bonnerjee) was a development economist whose international career included nine years at UNCTAD, along with work as a self-employed consultant to private business organisations. Remembered by her contemporaries as an intellectually vibrant and generous individual,[1] Graham was an Indian-born woman economist whose work reached deep into international institutions. However, her work has been elided from historical narratives of UNCTAD and the New International Economic Order (NIEO), possibly because it was institutionally rather than academically based. Graham’s prolific output consistently critiqued development debates as Global North-centred and dismissive of the South’s needs. The evidence of her public advocacy of NIEO has led international relations scholar and former UNCTAD colleague Thomas G. Weiss to portray her as ‘if not the mother, certainly the mid-wife of NIEO.’[2] This characterization reflects both the difficulty of winkling out the actual nature of Anila Graham’s institutional and intellectual agency in this crucial period in international history, beyond gendered metaphors, and establishing Graham’s significance as an international economic thinker.

The making of an Indian internationalist Graham

Born into an upper Brahmin family in Calcutta, Graham was the granddaughter of Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee (1844–1906), the first president of the Indian Congress.[3] After receiving a BSc economics degree from the University of Calcutta, she joined the London School of Economics (LSE) in the mid-1930s, where she obtained a MSc in Economics under Harold Laski’s supervision. Laski was a shining star in the interwar Labour Party whose engaging personality attracted several left-wing Indian students at the LSE, including Graham, whose Communist engagement antedated her coming to Europe.[4] A year before returning to India in 1938, Graham participated in a visiting trip to the Soviet Union.[5] Once back in India, Graham lectured at the University of Calcutta and collaborated with the local Communist Party, until in 1941 becoming Assistant Director of the British Government of India’s Supply Department.

With the hostilities over, Anila Graham returned to Britain. In 1946, she began advising private business organisations. She worked first with the British Export Trade Research Organisation as Head of its Information Section on Asia,[6] and left that position in 1948, apparently because of her membership in the Communist Party of Great Britain.[7] A short spell ensued at the Commerce Department of the Indian High Commission (1948–1952). Here she participated in various Commonwealth Raw Materials and Finance conferences and edited the bi-weekly journal Indian Trade and Industry. Graham then became head of research at the London Export Corporation (1953–1960), a private business consultancy founded by a Communist businessmen, Jack Perry, to foment trade with China.[8] In 1960, Graham set up her own consultancy, aptly titled Economic and Development Research Ltd. As well as publishing a Monthly Development Digest and writing for varied journals, she prepared reports for the Indian Chamber of Commerce in London, including a negative forecast of Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC). Arguing that the EEC’s common tariff would end Commonwealth preferences, Graham noted that India’s manufacturing exports would be adversely curtailed, robbing resources from its industrial development. The vested protectionist interests she perceived as being influential in the EEC prompted Graham to call for an Asian Common Market.[9]

Graham’s internationalist commitment dates at least from the early 1960s, when she joined the Economic Advisory Committee of the United Nations Association in London. Her first collaboration with the United Nations occurred in 1963 when she helped edit the proceedings of the United Nations Conference on the Application of Science and Technology for the Benefit of the Less Developed Areas.[10] In 1967, she joined UNCTAD’s Division for Conference Affairs and External Relations, as editor in its Editorial and Documents Control Unit. Until 1976, Graham was deeply involved in UNCTAD’s public relations efforts to gain support for its comprehensive programme redrawing North-South economic relations. We can trace the evidence of her endorsement of UNCTAD’s agenda of international commodity and shipping agreements, along with technology and patent transfers from North to South, in the many reports and articles on development economics that she wrote before joining UNCTAD.

Why Anila Graham is an international economic thinker

As an independent consultant with proven expertise of India’s economy, Anila Graham wrote (often for profit) reports on topical economic development issues that were circulated internationally. In turn, this made her a participant in academic and journalistic conversations about how to reform the international monetary and trade systems.[11] Well before her employment in UNCTAD, Graham’s caustic analyses of the dire prospects facing India’s economy if the prices of primary commodities continued to decline, reveal an understanding of the importance of joint international trade and monetary reform focused on opening up Global North markets to Global South manufactures.[12] Faced with increasing European protectionism in the form of the EEC, Graham embraced the possibility of creating regional economic groupings in the form of common markets in Latin America and Asia. Believing that international trade could be ‘a powerful instrument to forge economic development’, ahead of UNCTAD I (1964) Graham was cautiously hopeful about the capacity of concerted international action to provide the necessary ‘radical changes in the structure of world trade’.[13]

Realistic about the likely opposition to UNCTAD from developed countries, in 1964 Graham responded positively to Raúl Prebisch’s calls for a new international division of labour embracing preferences for the manufacturing exports of developing countries, rather than leaving them dependent on primary commodity exports.[14]In response to Prebisch’s view that compensatory finance schemes could only act as a palliative for countries experiencing weakening terms of trade, Graham’s writing reinforced the need for reform of the post-war Bretton Woods international monetary system, much as was being argued by the likes of the better known Robert Triffin.[15]The concern was that existing gold and dollar reserves would not sufficiently back expanding world trade and investment, especially in the case of monetary and/or fiscal crises. Faced with the prospect of a liquidity shortage, developed countries would restrict imports and foreign aid disbursements, which, in turn, would damage developing countries already hostage to recurrent balance-of-payments challenges. Criticising ‘the characteristic inward-looking economic philosophy of the Continental Europeans’, Graham juxtaposed Global South needs with varied Global North-framed monetary proposals. Any reform to increase international liquidity, she concluded, should ensure that newly created reserves would be given to developing countries not as credit or aid but as gifts.[16]

Once at UNCTAD, Anila Graham was a perfect advocate for its agenda. While recognising that the initial promise of UNCTAD I had not been met, she praised it for exploding the neoclassical myth that in world trade all countries were economically equal.[17]On the eve of UNCTAD II (1968) in New Delhi, she summarised UNCTAD’s principle of action as extending to the international sphere the right of nation-states to intervene ‘in the operation of the free market to improve social conditions and income distribution.’[18] Reaching out to wider audiences, Graham wrote articles clarifying UNCTAD’s aims and related them to Indian development issues.[19] She was also concerned with more administrative tasks such as editing the proceedings of the Group of 77 ministerial meetings (Algiers in 1967, Lima in 1971, Manila in 1976) or serving as rapporteur to a 1974 working group on external financing led by Hans Singer.[20]

After leaving UNCTAD in 1976 and resuming her career as an independent advisor, Graham continued to regularly publish on NIEO. Aside from providing synthetic overviews of successive UNCTAD conferences and their failings,[21] Graham relayed UNCTAD’s efforts to facilitate North-South technology transfers and lessen the South’s scientific and technical dependence on developed countries’ private interests.[22] Similarly, once at the onset of the 1980s external debt crises began to loom large on the horizon of developing countries, Graham renewed UNCTAD’s pleas for using debt restructuring and relief to improve developmental prospects in the South.[23] She was a stark critic of the neoliberal trickle-down assumption that market mechanisms would transmit prosperity to developing countries, participating for instance in the 1984 counter-summit to the G7, The Other Economic Summit.[24] Through the 1980s, Graham remained active within the United Nations Association in London and even after closing her consultancy in 1991, she continued to publish critiques of mainstream development economics.[25]

[1] Michael E. Tigar, Sensing Injustice: A Lawyer’s Life in the Battle for Change, 100.

[2] Thomas G. Weiss, Multilateral Development Diplomacy in UNCTAD: The Lessons of Group Negotiations, 1964–84 (London: Macmillan, 1986), xiii.

[3] The following biographical information is based on the potted biographies Graham wrote for her publications and in: Malcolm Harper, ‘Obituary. Anila Graham: UN economist fighting for international justice’: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2004/nov/18/guardianobituaries(retrieved on 10 March 2023).

[4] Brant Moscovitch, ‘Harold Laski’s Indian students and the power of education, 1920–1950’, Contemporary South Asia, 20:1 (2012) 33–44; and Sumita Mukherjee, Nationalism, Education and Migrant Identities: The England-returned (New York: Routledge, 2009).

[5] Harper, op. cit.

[6] J. A. P. Treasure, ‘The British Export Trade Research Organisation: 1945–1952’, The Manchester School, 21:2 (May 1953), 118–139.

[7] Harper, op. cit.

[8] On Jack Perry and the London Export Corporation, see: Valeria Zanier, ‘Forging new meanings of Europe. The cross-ideological logic of Western Business Trade Associations (BIAs) promoting trade with Mao’s China’, Business History. Available in https://doi-org.eui.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/00076791.2022.2154340 (retrieved on 18 March 2023).

[9] Anila Graham, British Membership of the Common Market…What Will It Mean to India’s Trade (London: Economic and Development Research Limited, 1962).

[10] United Nations, Science and Technology for Development. Report on the United Nations Conference on the Application of Science and Technology for the Benefit of the Less Developed Areas. Volume VIII: Plenary Proceedings, List of Papers and Index (New York: United Nations, 1963), iii.

[11] For two contrasting reviews of her work: ‘International Liquidity and the Developing World’, The Statist, 188 (1965), 1084; Arthur Hazlewood, ‘Aid, Trade and All That’, International Affairs, 41:2 (April 1965), 278–286.

[12] Graham, British Membership. See also a recap of Graham’s views in: ‘India’s Plight Underscored’, The Christian Science Monitor (13 March 1966), 10.

[13] Anila Graham, Break down the Barriers: Trade, Aid and International Development (London: United Nations Association of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 1964), 1, 37.

[14] Ibid.

[15] On Triffin’s quest for international monetary reform: Ivo Maes, Robert Triffin: A Life (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021), 113–150.

[16] Anila Graham, International Liquidity and the Developing World (London: Economic and Development Research Limited, 1966).

[17] Contemporary observers and historians agree that UNCTAD I, although a political and institutional success for developing countries, failed to deliver any major direct economic results in the form of an international commodity agreement, tariff preferences, or long-term compensatory finance: cf. A. S. Friedberg, The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development of 1964: The Theory of the Peripheral Economy at the Centre of International Political Discussions (Rotterdam: Universitaire Pers Rotterdam, 1968), 198–201; with John Toye and Richard Toye, The UN and Global Political Economy: Trade, Finance, and Development (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), 201–203.

[18] Anila Graham, ‘The Aims and Activities of Unctad, Bank of London & South America Review, 1 (January 1968), 4.

[19] Ibid., 2–11; and ‘The Export Growth of Agricultural Commodities in Indian International Trade’, in Ashok V. Bhuleshkar, Indian Economic Thought and Development (Bombay: Popular Prakashan), 1969, 157–172.

[20] Hans Singer and Anila Graham, ‘Report of the Working Group on External Financing: Trade, Aid and Other Forms of International Co-Operation’, World Development, 2:2 (February 1974), 117–121.

[21] Anila Graham, ‘Die neue internationale Wirtschaftsordnung—eine schwindende Vision?’, Vereinte Nationen: German Review on the United Nations, 27:5 (October 1979), 162–167.

[22] Anila Graham, ‘The Transfer of Technology: A Test Case in the North-South Dialogue’, Journal of International Affairs (Spring–Summer 1979), 1–17.

[23] Anila Graham, ‘Debt and Development: Need for Adequate Measures’, Development and Peace, 1 (Spring 1980), 106–117.

[24] Anila Graham, ‘Trickling down and out’ in Paul Ekins (ed.), The Living Economy: A New Economics in the Making (London and New York: Routledge, 1986), 18–20.

[25] Harper, op. cit; Anila Graham, ‘Reviewed Works: From Global Capitalism to Economic Justice. An Inquiry into Elimination of Systemic Poverty, Violence and Environmental Destruction in the World Economy by Arjun Makhijani’, Medicine and War, 8:4 (October-December 1992), 305–307.

Reference anything from this site as:

Sampaio, Guilherme (2023) 'International Economic Thinkers-Profile: Anila Graham', ECOINT IET Profile #2, available at: https://www.ecoint.org/post/profile-of-anila-graham-1916-2004